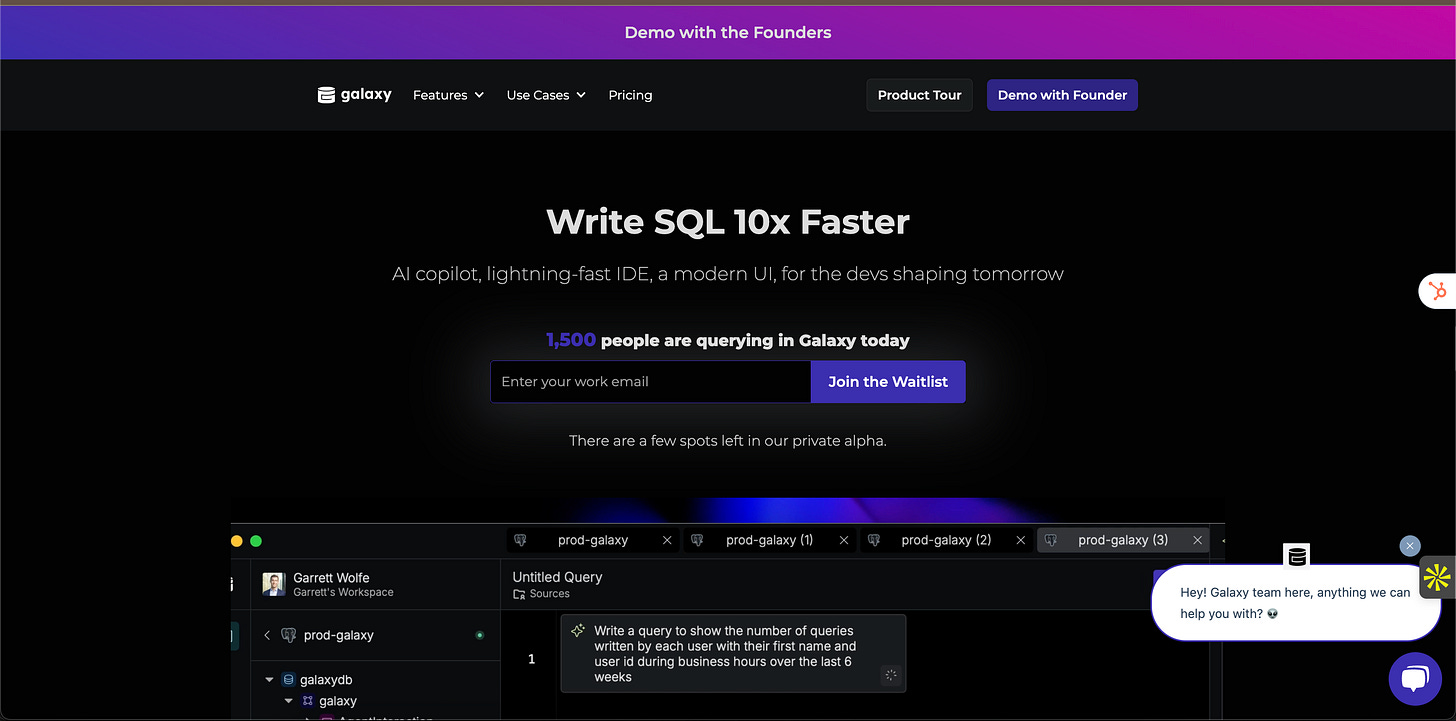

Starting a company is a chaotic mix of intuition, timing, and conviction—there’s no perfect moment, only the courage to leap. This blog walks through my personal journey of founding Galaxy, covering everything from identifying a problem and choosing cofounders to validating ideas, building MVPs, raising money, and managing the emotional rollercoaster.

Hey everyone, I'm sharing a personal post from my personal blog, which you can find the most up to date version for here. But recopying here for ease :)

For some, joining a startup is as far as their risk appetite will take them. But for others, they may start to feel an itch, and that itch begins to grow. I got that itch. I have friends who have gotten that itch. And the question you are probably asking yourself is

When and how do I know to scratch that itch!?

Starting a company is no small undertaking, so it is understandable that people want to make a really educated decision on how / when to do it.

Before we even get into it, the TLDR is that there is never really a good time to do it.

The reality is, you need to take a leap of faith. But in this little stream of consciousness piece I wrote below, I’ll try to walk you through my journey (and that of my cofounders as well), so you can see how we established the foundations of our shared vision for Galaxy.

The first step in starting any company is identifying a problem you want to solve. When trying to do this, think deeply about your day-to-day workflows, areas you’re interested in, and more. Outside of your experience, talk to friends, family, colleagues, and more - there is a wealth of companies waiting to be built - it’s no coincidence we see so many companies started every year.

There are a few routes you can go when identifying an area:

Trying to solve a problem you have experienced firsthand is the most compelling reason to start a company.

There is a concept in the VC world called founder market fit → this is a heuristic used to describe the relationship between the founder and the problem they are trying to solve. Is this person the right person to solve the problem? Typically, those are the founders that win, especially when there is competition, because they know what the product needs to be to be successful.

Mitch and Leon have worked extensively with data over the last 5+ years across teams at Bloomberg, Parkmobile, Flock Safety, and Unify. They have built, procured, and used dozens of data systems and worked with hundreds of other data practitioners. For them to team up to solve this problem makes a heck of a lot of sense.

For me to start a company like Galaxy without them would not make a ton of sense :)

We see this theme of founder market fit over and over again:

While this one is a bit more difficult in execution, it has become more common over the last few years. Jump into a random field that desperately needs innovation, shadow real people in the space for a few months, and observe their workflows, and create a solution to solve their problems. Do market research or go talk with people that you want to serve and figure out how to improve their day-to-day.

Mitch and I have had dozens of ideas that we have had or know others have. Listing a few of our ideas below:

Garrett - a better workflow platform for recruiters / headhunters (I hate their poorly fit automated emails and job recommendations), a financial wiring platform for large financial transactions, etc.

Mitch - a platform that allows you to bake PLG into your product as PLGaaS, a 24/7 worldwide gameshow with prizes, etc.

Leon -

I’m not saying solo founders can’t win. Plenty have. But if you're reading this and don’t have a chip on your shoulder the size of a small boulder or a cult following on Twitter - you probably want a cofounder.

Cofounders make the highs higher and the lows survivable. They keep you honest when you're too hyped about a feature no one wants. They push you when you're spiraling over a bug no one will notice. They’re your mirror and your momentum.

So how do you choose one?

Here’s the framework I’ve come to believe in:

Every cofounder relationship, no matter how strong, will hit moments of friction. That’s not a red flag - it’s the cost of building something that matters. What matters is how you work through it. For us, we committed early to directness: no side conversations, no backchanneling, no simmering. If something feels off, we bring it up - even if it’s awkward. We also try to assume positive intent. If someone’s pushing back, it’s because they care. One thing that’s helped a ton: separating what we’re deciding from how we’re deciding. Sometimes the disagreement isn’t about the idea - it’s about how we’re making the call. Having a clear framework for how decisions get made has helped us move fast without fracturing trust. The three of us have had disagreements and worked thru them with time and care. And as time goes on, I trust that all three of us will continue to prioritize our shared relationships :) I also go to therapy to try to just be a better person, and that certainly helps. I highly recommend it :)

Leon, Mitch, and I complement each other really well. Mitch and Leon are both incredible engineers with deep experience in the space, and I’ve spent my whole life around GTM, investing, and company-building. We’ve built mutual trust and have hard conversations head-on. And we really like working together, which might sound fluffy but turns out to be one of the most important parts. Mitch and I are very high energy and passionate, and Leon is extremely grounded. It’s a great combo.

Mitch absolutely refuses to add some fun colors to Galaxy after the AI copilot generates SQL. I’m going to get him to swing in my direction soon :)

It is of the utmost importance to validate the problem and its severity before you go gung-ho on building a solution. Talk with people in your network who may be familiar with this problem or feel it directly. Ask them:

Being a less-technical member of the team who hasn’t felt the problem to the same extent Mitch and Leon had, while also being a ex-investor who generally is skeptical of dev-tools, I immediately started doing work to ask people I know about this problem.

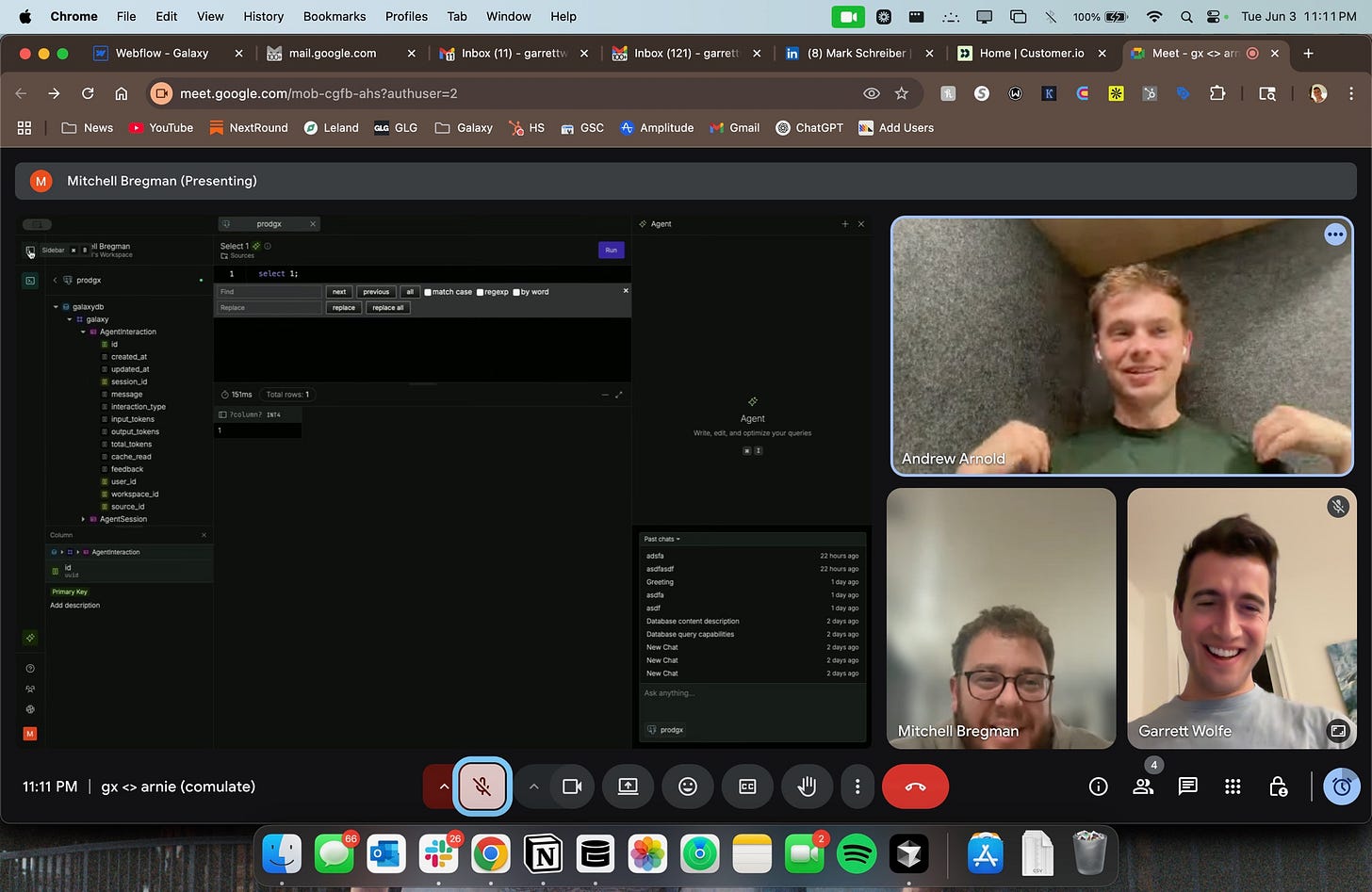

In the days after my first conversation with Mitch, I setup time to chat with dozens of friends from college, ex-coworkers and more. People like Brendan Quinlan, Branick Weix, Andrew Arnold, Luis Fornes, Riley Cohen, Garrett Neff, Riley Hockett, Billy Ramundo, Elie Farah, Stu Baker, Liran, Matt Gigolio.

Anyone that had a point of view of exposure to the problem space I wanted to talk to. We recorded all the calls and began to build an understanding of what people were and were not frustrated by, and what a solution could potentially look like.

Now it’s time to be really thoughtful and brainstorm a solution. Take time to do research and draw up what you think a solution could be. Talk with real stakeholders and see what they might imagine a solution could be. Begin to outline the answers to a few key questions

Mitch and I had been talking about the idea that was Galaxy very casually but eventually one Saturday we met up at L’antica da Michele in the West Village with our third co-founder Leon to discuss the idea and what it would look / feel like. Over some pizza, pasta, and espresso martinis, we talked through much of the above. In the days that followed we ironed out many of these areas and planned how we would make this vision come to life.

Some problems require venture capital funding to solve. I say “some” because not every problem requires millions of dollars of backing and hypergrowth.

A super quick lesson on VC firms and how the make money. Venture capital firms make money by investing in the next great companies and those investments (companies) becoming liquid at some point, either through an acquisiton, or ideally - IPOing and going public!

Venture capital investing is extremely risky. 99.9% of all startups fail, and so for the most part - any investment that a VC makes is probably going to go out of business. VCs know this (and plan for it), and as such hope that 1-2 of their investments create all of their profits.

This is called Venture Power Law. VCs are in the business of betting on the next big thing. It doesnt work for them to pick a bunch of small positive outcomes - they need the enormous ones.

This is important because if your idea has a total addressable market that is too small - venture capital firms may not be wiling to invest in it, and thus you will need to bootstrap the company yourself (meaning you probably can’t pay yourself a salary, hire, spend money on things, etc.).

At a certain point post brainstorming the solution, if you are planning on quitting your job and starting this company full-time, assuming you want/need to pay yourself a salary - you probably need to raise money from VCs in order to do so. It may make sense to have some very casual conversations with venture capital firms to also validate your idea and see if they’d be excited about it.

Venture Capital is a relationship-driven business - reach out to friends, family, and others who might be connected with various VCs to have a conversation with them. If you’re interested in meeting with VCs and want help getting in touch with them, feel free to reach out to me on Linkedin or at my email and i’d be happy to help out.

VCs will be very direct - prepare for these conversations and take notes on their questions. They have experience listening to thousands of pitches and its likely they’ve seen an idea like yours in the past. Prepare for them to ask deep questions on the problem-space, the market size, and even go-to-market strategy.

Given my venture background I had spoken with a number of friends in the VC world to gauge interest and determine if Galaxy would be interesting.

We spent a considerable amount of time working on, practicing, and refining our pitch, especially after conversations with VCs, customers, and more to double down on what was resonating.

In the first copy of this blog I debated putting this at the end, but I felt bad for making people read all the way to the end before talking about one of the most interesting parts of this piece.

For most people, they will be unable to do the portions of this post that come after this section (building, marketing and launching) while still at their normal day job. It’s not only tough to find the time to build and sell, but you also will run into roadblocks from your existing employer.

Thus, at some point, you will need to make a call. If you were reading this in order to get the answer to your burning question “how do I know when I should quit and go out on my own full time?”, I unfortunately don’t have a good answer for you (lol)

The brutal reality is that no matter how much discovery, building, and validation you do - startups are risky for a reason - there is never certainty. All you can do is develop your own excitement and conviction, find a great team to build with, and a handful of other small things. Then, you have to go with your gut and take the leap of faith.

That said, there are a few questions you can ask yourself in the final inning and are worth discussing with your cofounders to ensure you set yourself up for the best odds of success:

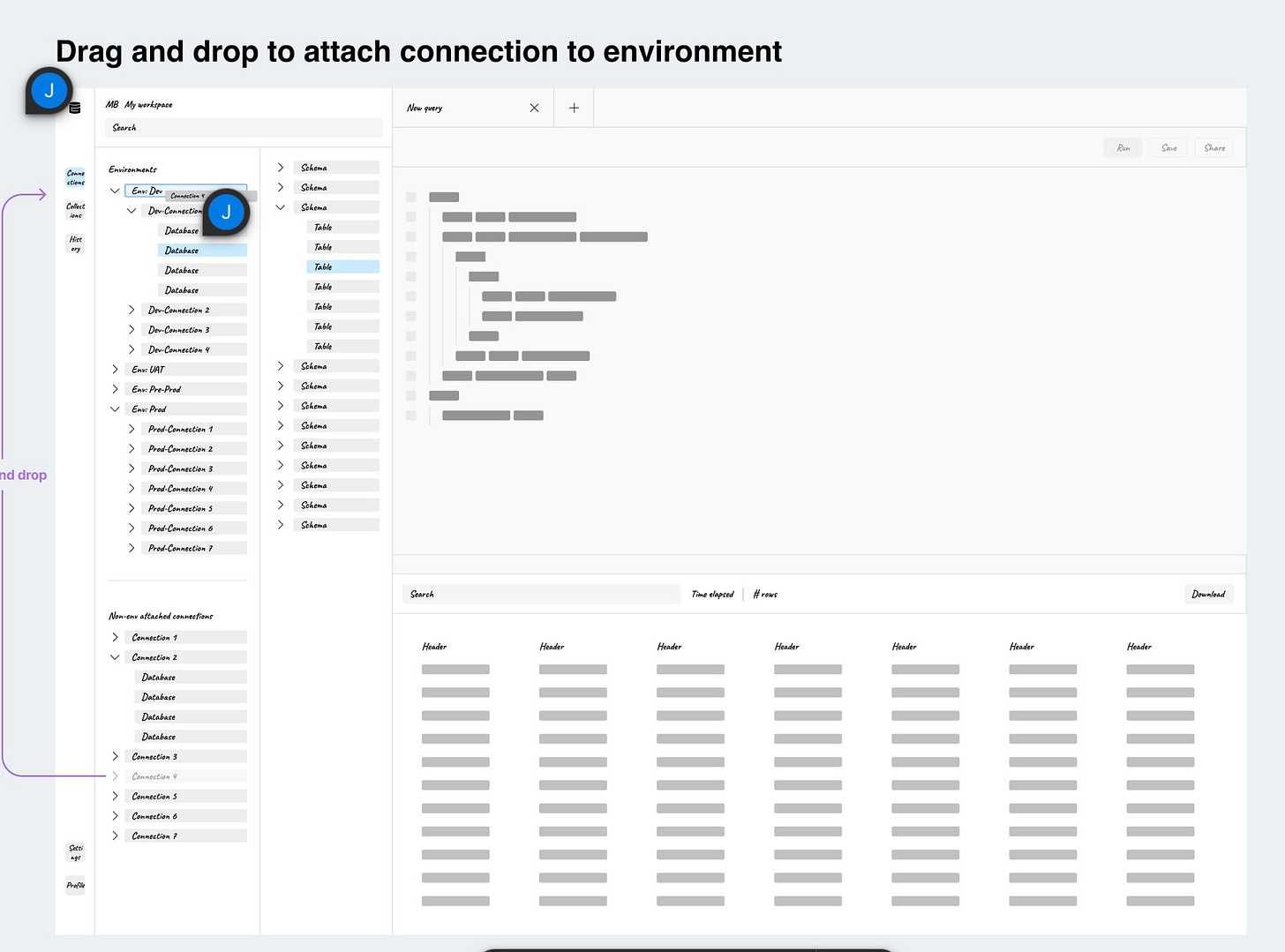

Once you identify the problem, validate it, and brainstorm a solution - it comes time to methodically plan out what a minimum viable product (MVP) could be. This is your best way to test the waters and determine if what you are building is of value to the people you intend to sell to. As a team, sit down and think through what the path to building an MVP looks like

This portion was predominantly comprised of Mitch and Leon discussing what we wanted to build and how we were going to build it. Once the initial roadmap for the MVP was planned, together we went super deep on each feature, how necessary it was, and any risks we could foresee inherent in it.

We actually put together an extremely thorough spec of each phase of building, how much time and people it would require, expected $ cost, and the key features to be delivered. We also identified each risk we might run into.

The best teams divide and conquer responsibilities. For many of you reading, you’re probably wondering how to de-risk your decision to start a company. My recommendation is to create a team comprised of someone who can build, and someone who can sell. While person A is building, person B should de-risk the build by continuing to validate the problem and also pre-emptively marketing and selling the solution.

The last thing you want is for your hardworking technical cofounder to spend months building a product only for you to then have to go find people to sell it to and use it.

How do you sell someone something before it exists? This is the art of selling - people have been selling promises and vision since the beginning of time. There is always “the next thing to build” and the best sales people can sell it before it even exists :). Begin to push on your go-to-market strategy to drum up early interest in your product, so that when the MVP is complete, you can get these early users onto it.

So how do we do this? There’s three main components: find people to sell to, create things to show them, and offer early adopter perks.

We started by leveraging our networks and reaching out to devs we know. We then moved to tap Alumni networks and even looked thru Reddit communities. Then we literally started reaching out to random people and tried pitching Galaxy to them. Hundreds of our customers today are people I cold DM’ed on Linkedin :)

Our team spent a few grand iterating on designs with a contractor. This was really great for showing to prospects and getting people excited. I would definitely recommend building doing something like this. I also began to explore Webflow and how to build a website we could point people to. This was a really big value driver for us.

Most early stage teams need to give their products away for free at the beginning to get feedback. If you’re lucky, some customers feel the pain point you are promising to solve so severely that they will actually agree to pay for a solution.

If you’re super lucky, some customers will agree to be Design Partners - which is an actual contractual agreement that says a company will be customers of yours for some set period of time and will give you logo rights and a case study in exchange for early access to the product and new features, priority support, and some discount on the full product once the design partnership is over.

Use templates like the Common Paper one to structure formal relationships with your Design Partners :)

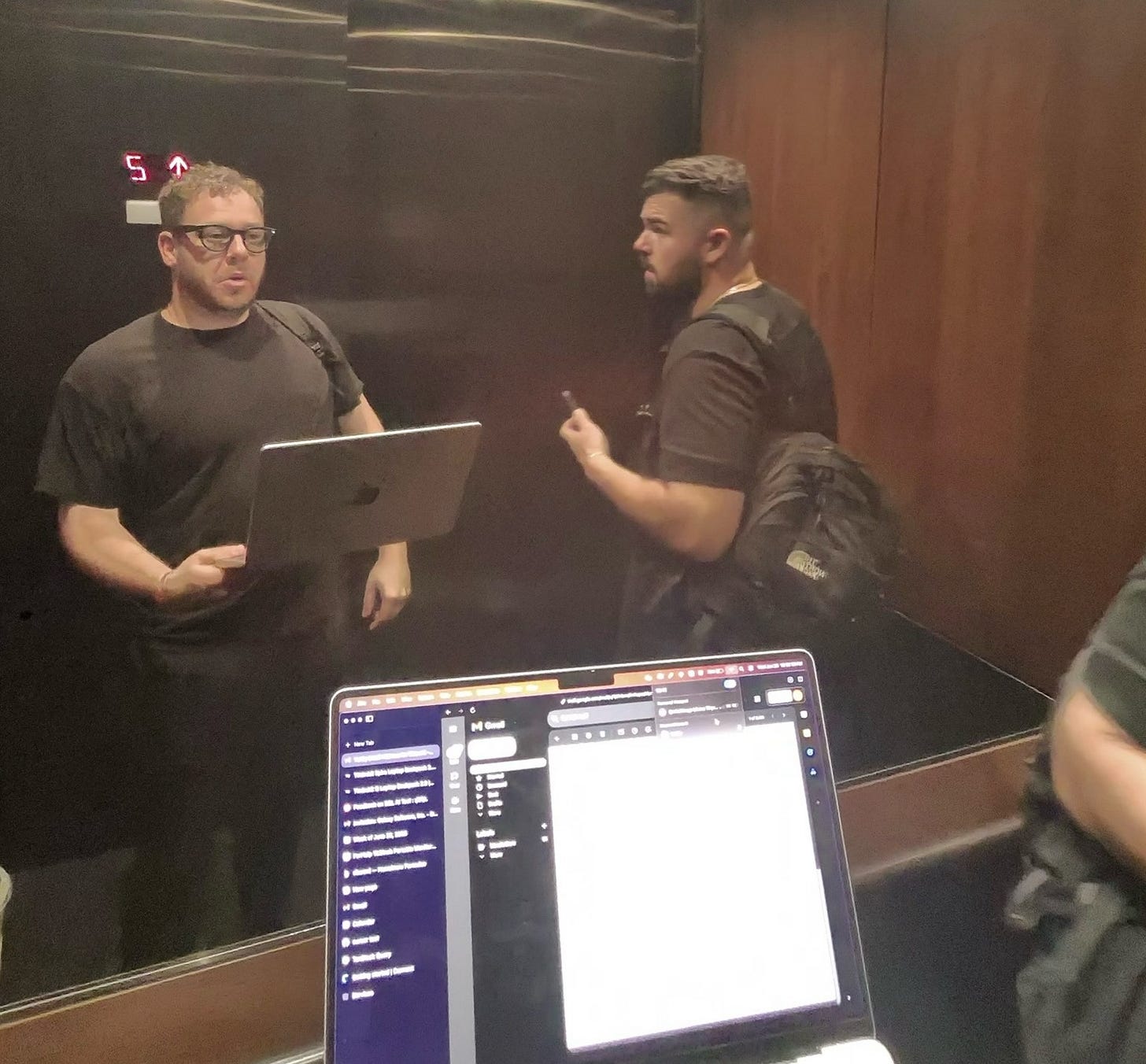

Myself, Mitch and Leon have spent hundreds of hours on the phone with developers and data practitioners sharing our vision for the product and trying to convince them on being a Design Partner.

To do this we would spend 15-30 mins on the phone with them doing discovery, sharing our vision, and if they were a really strong fit - we would then proceed to ask them to be a Design Partner and tell them they would get free access to the product, extra AI credits, and other perks.

This is the fun part. It’s time to plan the launch! Launching your product is a huge milestone, and one that you and your team should celebrate. But before you do that, there’s tons to do. With any launch, you want to help your product really hit takeoff velocity and give it the best chance of having a viral launch. Achieving such an outcome does not take luck - its actually tons of preparation and meticulous planning. Some things to consider planning out:

Our team has spent countless hours talking about launch. Things like our marketing, social posts, and more have been talked about endlessly for hours and hours upon end.

Don’t skip this part and really tap your network to help support you and engage with your posts as much as possible. You only have one first launch!

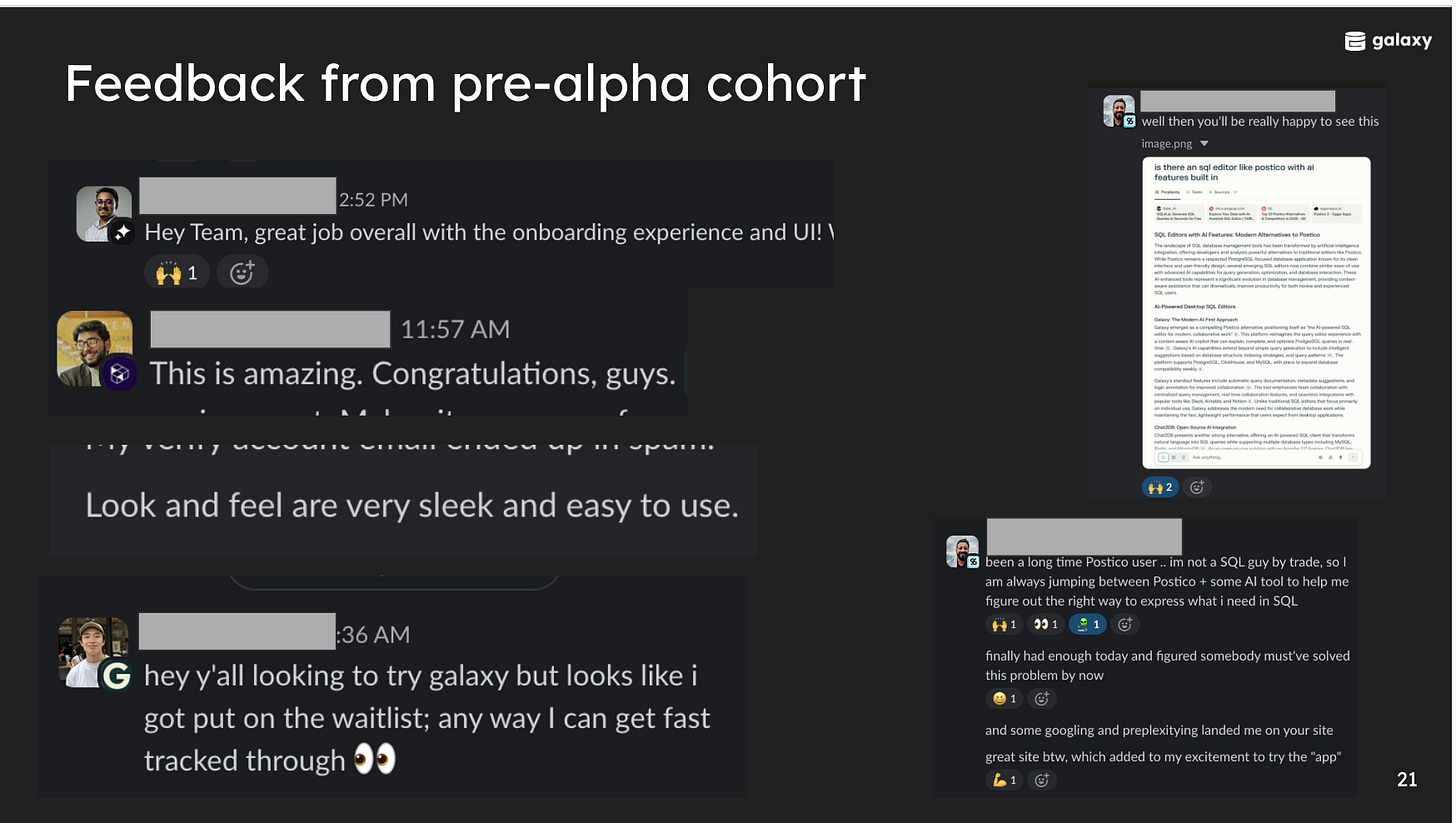

We actually did a poor job determining the level of support we would be able to offer to customers during our Alpha launch and also let in too many individuals to the product. This created a sub-par onboarding experience and one we definitely learned from. Going forward, I mapped out what customer success and support would look like, as well as planned which users would get access to the product in phases.

Once you’re through the initial launch, it’s important to collect feedback but also identify and choose the customers that you want to build for. When I imagine this, funny enough I think of entering a gravitational slingshot. As tacky as it sounds, you want to identify your best fit customers, and iterate with them super quickly. Collect feedback as quickly as possible, ship fast AF, and get them a product they’d die to have sooner rather than later. This is absolutely key and you want to turn them to evangelists :)

This part rarely gets talked about, but it’s something every founder should think about. There’s so much survivorship bias in startup land that we all end up romanticizing sticking it out forever. But knowing when to stop - or pivot - is just as important as knowing when to start.

There’s no perfect formula, but here are some signals I think about:

We didn’t write out hard exit criteria at the beginning - but we probably should have. Even a rough sketch would’ve helped us frame decisions better. That said, we constantly gut-checked ourselves on whether we were seeing the signals we wanted to see from users, and that helped guide our next steps.

We did however write out what we would need to see to make the jump - tons of interest, hints of investor taste, and a well paved roadmap and way to get there.

No one really prepares you for the emotional whiplash of starting a company. One day you feel like you're building the next unicorn - the next, you’re spiraling because someone didn’t respond to your email. It’s a constant push and pull between belief and doubt, momentum and inertia. The highs are higher than anything you’ve felt in a normal job, but the lows can be isolating and brutal. I’ve had mornings where I felt unstoppable and evenings where I questioned everything. You have to build a kind of emotional endurance - learning to stay steady through both chaos and silence. Surrounding yourself with people who remind you why you’re doing this (and who still like you even if the idea flops) is critical.

I remember when we first sent our deck out to VCs and I literally laid down on my bed and was freaking out and forecasting our odds of failure; like

It was a hilarious reality of building.

I am nowhere near being successful just yet, and the odds of failure are high; but its about the journey and having a good time while building something that matters!

Fundraising is one of those things that looks easy from the outside (“just raise a pre-seed!”) but is wildly time-consuming and emotionally exhausting in practice. Everyone’s winging it, even the ones who look like they’re crushing.

So here’s how we approached it:

We didn’t wait until we had a deck to start talking. I started reaching out to VCs I had relationships with from my investor days and just… floated the idea. Casual “hey, we’re noodling on something” coffees. It gave us signal on who was actually excited about the space.

You need a deck because VCs need something to forward to their partner. But the best conversations don’t follow your slides. They follow your energy. Your conviction. Your story.

A lot of people try to pitch a $10B vision without showing any path to $1. We tried to balance: here’s the world we see, here’s how we’ll get there, and here’s why we’re the right team to build it.

FOMO is real. Try to have all your VC conversations in a 7–10 day window. The more things overlap, the more momentum you build.

We were lucky to get a few strong signals early from VCs who had conviction in the space. I leaned hard on warm intros and clarity of story. I also made sure to follow up fast - investors are evaluating how quickly you move just as much as the idea itself.

If you’re fundraising, feel free to DM me — always happy to help with intros, deck reviews, or just talk strategy.

You will make a thousand mistakes. That’s the deal. But here are a few we made that might save you some pain:

We got excited. People wanted to try Galaxy, and we said yes to a lot of them. The result? A flood of feedback we couldn’t act on fast enough and onboarding experiences we weren’t proud of.

➡️ What we’d do now: Start with 3–5 users, perfect the loop, and then widen access.

LinkedIn, Twitter, Reddit, SEO, cold outbound, community — we tried to spin up all of them fast. Which meant none of them were amazing.

➡️ What we’d do now: Pick one or two GTM channels and go deep before layering in more.

As the Twitter and LinkedIn shitposters say (and lowkey the guys at Cluely):

You can just do things

Go out and do them

.avif)